The Economics of Large Language Models

The Cost of ChatGPT-like Search, Training GPT-3, and a General Framework for Mapping The LLM Cost Trajectory

TLDR

LLM-powered search is already economically feasible: As a rough estimate, the cost of performant LLM-powered search is on the order of ~15% of estimated advertising revenue/query today, on top of the existing search cost structure

But economically feasible does not mean economically sensible: The unit economics of LLM-powered search are profitable, but adding this functionality for an existing search engine with $100B+ of search revenue may mean $10B+ of additional costs

Other emerging LLM-powered businesses are highly profitable: Jasper.ai, which generates copywriting with LLMs, likely has SaaS-type (75%+) gross margins

Training LLMs (even from scratch) is not cost prohibitive for larger corporations: Training GPT-3 would only cost ~$1.4M in the public cloud today, and even state-of-the-art models like PaLM would cost only ~$11.2M

LLM costs will likely drop significantly: Training and inference costs for a model with comparable performance to GPT-3 have fallen ~80% since GPT-3’s release 2.5 years ago

Data is the emerging bottleneck for LLM performance: Increasing model parameter count may yield marginal gains compared to increasing the size of a high-quality training data set

Table of Contents

Motivation

The spectacular performance of large language models (LLMs) has led to widespread speculation on both the emergence of new business models and the disruption of existing ones. Search is one interesting opportunity, given that Google alone grossed $100B+ of revenue from search-related advertising in 2021.1 The viral release of ChatGPT — an LLM-powered chatbot producing high-quality answers to search-like queries — has prompted many questions on the potential impact on the search landscape, one being the economic feasibility of incorporating LLMs today:

One alleged Google employee suggested on HackerNews that we would need 10x cost reduction before LLM-powered search can be viably deployed2

Meanwhile, Microsoft is expected to launch a version of Bing equipped with LLMs by March,3 and search startups like You.com have already embedded the technology into their products4

Most recently, the New York Times reported that Google will be unveiling a search engine version with chatbot-like functionality this year5

A broader question is: How economically feasible is it to incorporate LLMs into current and new products? In this article, we tease out the cost structure of LLMs today and provide a sense of how it will trend going forward.

A refresher on how LLMs work

Although later sections get more technical, we won’t assume any machine learning familiarity. To level set on what makes LLMs special, we provide a brief refresher.

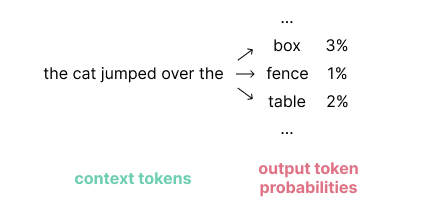

Language models predict the likelihood of an output token, given some context:

(In practice, tokens are generally subwords: i.e. “happy” might be broken up as two tokens such as “hap,” “-py”)

To generate text, language models repeatedly sample new tokens based on the output token probabilities. For example, in a service like ChatGPT, the model begins with an initial prompt that includes the user’s query as context and generates tokens to construct the response. As each new token is generated, it is appended to the context window to inform the next iteration.

Language models have existed for decades. What has propelled the performance of the LLMs we know today is the implementation through efficient deep neural networks (DNNs) with billions of parameters. The parameters are matrix weights that are used for both training and making predictions, with the number of floating point operations (FLOPs) generally scaling with the parameter count. These operations are computed on processors optimized for matrix operations, such as GPUs (graphics processing units), TPUs (tensor processing units), and other specialized chips. As LLMs grow exponentially larger, these operations demand significantly greater computational resources, which are the underlying driver of LLM costs.

How much would LLM-powered search cost?

In this section, we estimate how much it costs to run an LLM-powered search engine. How such a search engine should be implemented remains an area of active research. However, we consider two approaches to assess the cost spectrum to provide such a service:

ChatGPT Equivalent: An LLM trained over a vast training dataset, storing knowledge during training into the model parameters. During inferencing (i.e. using the model to generate output), the LLM does not have access to external knowledge.6

Two key drawbacks are:

This approach is prone to “hallucinating” facts

The model’s knowledge is stale, containing only information available up to the last training date

2-Stage Search Summarizer: An architecturally similar LLM that can access traditional search engines like Google or Bing at inference time. In the first stage of this approach, we run the query through a search engine to retrieve the top K results. In the second stage, we run each result through the LLM to generate K responses. The model then returns the top-scoring response to the user.7

This approach improves over the last by:

Being able to cite its sources from the retrieved search results

Having access to up-to-date information

However, for an LLM of comparable parameter count, this approach suffers from requiring a greater computational cost. The cost of using this approach is also additive to the existing costs of a search engine, given that we piggyback off of existing search results.

First-order approximation: foundational model APIs

The most direct method of estimating cost is through the list prices of existing foundational model APIs on the market, understanding that the pricing for these services embeds a premium to cost as profit margin to the providers. One representative service is OpenAI, which offers text generation as a service based on LLMs.

OpenAI’s Davinci API, powered by the 175B parameter version of GPT-3, has the same parameter count as the GPT-3.5 model that powers ChatGPT.8 Inferencing from this model today costs ~$0.02/750 words ($0.02/1000 tokens, where 1000 tokens correspond to ~750 words); the total number of words used to calculate pricing comprises both the input and output.9

We make a few simplifying assumptions to arrive at estimates for what we would pay OpenAI for our search service:

In the ChatGPT equivalent implementation, we assume that the service generates a 400-word response against a 50-word prompt, on average. To produce higher-quality results, we also assume the model samples 5 responses per query, picking the best response. Thus:

In the 2-Stage Search Summarizer implementation, the response generation process is similar. However:

The prompt is significantly longer since it contains both the query and the relevant section from the search result

A separate LLM response is generated for each of K search results

Assuming K = 10 and each relevant section from the search result is 1000 words on average:

Assuming a cache hit rate of 30% from optimizations (low-end of Google’s historical cache hit rate for Search10) and OpenAI gross margins of 75% (in-line with typical SaaS) on cloud compute cost, our first-order estimate implies:

By order of magnitude, the estimated cloud compute cost of the ChatGPT Equivalent service at $0.010/query lines up with public commentary:

In practice, however, the developer of an LLM-powered search engine is more likely to deploy the 2-Stage Search Summarizer variant given the aforementioned drawbacks (i.e. hallucinating facts, information staleness) of ChatGPT Equivalent.

In 2012, Google’s Head of Search indicated that the search engine processed ~100B searches/month.11 From 2012 to 2020, per the World Bank global internet penetration increased from 34% to 60%.12 Assuming that search volume grows proportionately, we estimate 2.1T searches/year against ~$100B of search-related revenue13, arriving at an average revenue of $0.048/query.

In other words, our estimated cost of $0.066/query is ~1.4x the revenue per query based on the 2-Stage Search Summarizer approach. To refine our estimate further:

We anticipate ~4x lower cost through optimizations like 1) quantization (using lower precision data types), 2) knowledge distillation (training a smaller model that learns from the larger one), and 3) training smaller but equally performant “compute-optimal” models (discussed in greater detail later)

Running the infrastructure in-house vs. relying on a cloud provider offers another ~2x lower cost, assuming ~50% gross margins on cloud computing

Net of these reductions, the cost of incorporating performant LLMs in Search is on the order of ~15% of query revenue today (in addition to existing infrastructure costs).

A deeper look: cloud compute costs

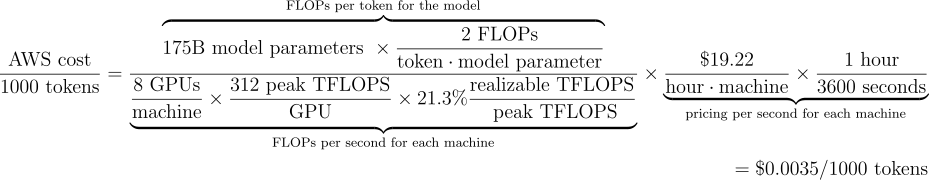

State-of-the-art LLMs today generally apply a comparable model architecture (most often, decoder-only Transformer models), with the computational cost (in FLOPs) per token during inference equal to ~2N, where N is the model parameter count.14

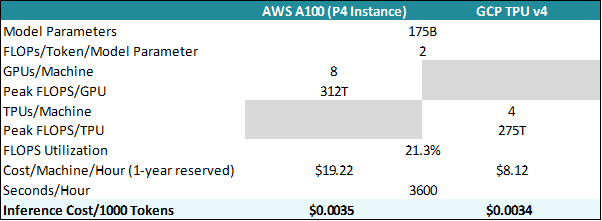

The Nvidia A100 is currently the most cost-effective GPU option from AWS, and the effective hourly rate of an AWS P4 instance with 8 A100s is $19.22/hour if reserved upfront for 1 year.15 Each A100 delivers a peak 312 TFLOPS (teraFLOPs/second) FP16/FP32 mixed-precision throughput, the key metric for LLM training and inferencing.16 FP16/FP32 mixed precision refers to performing operations in 16-bit format (FP16) while storing information in 32-bit format (FP32). Mixed precision allows for higher FLOPS throughput due to the lower overhead of FP16, while maintaining the numerical stability needed for accurate results.17

We assume 21.3% model FLOPS utilization, in-line with GPT-3’s during training (more recent models have achieved higher efficiency, but utilization remains challenging for low latency inference).18 Thus, for a 175B parameter model like GPT-3:

We also apply the same calculations based on GCP TPU v4 pricing, with similar results:19

Our estimated cost of $0.0035/1000 tokens is ~20% of OpenAI’s API pricing of $0.02/1000 tokens, implying ~80% gross margins assuming that the machines are never idle. This estimate is roughly in-line with our earlier assumption of 75% gross margins, thus offering a sanity check to our ChatGPT Equivalent and 2-Stage Search Summarizer search cost estimates.

What about training cost?

Another hot topic is what it would cost to train GPT-3 (175B parameters) or more recent LLMs such as Gopher (280B parameters) and PaLM (540B parameters). Our framework for estimating compute cost based on the number of parameters and tokens also applies here, with slight modifications:

Training cost per token is generally ~6N (vs. ~2N for inference), where N is the LLM parameter count20

We assume model FLOPS utilization of 46.2% during training (vs. 21.3% in inference previously), as was achieved by the 540B parameter PaLM model on TPU v4 chips 21

GPT-3 has 175B parameters and was trained on 300B tokens. Assuming we use GCP TPU v4 chips as Google did with the PaLM model, we estimate the cost of training today as only ~$1.4M.

We can also apply this framework to get a sense of what it would cost to train some of the even larger LLMs:

A general framework for mapping the cost trajectory

We summarize our framework for deriving LLM inference or training cost as follows:

(where “N” is the model parameter count and “processor” refers to either a TPU, GPU, or another tensor processing accelerator)

It follows that assuming LLM architectures remain similar, the cost of inference and training will change based on the variables above. We’ll consider each variable in detail, but the key takeaway is the following:

Training or inferencing with a model that is as capable as GPT-3 has gotten >80% cheaper since its release in 2020.

Parameter count efficiencies: the myth of 10x bigger models every year

One of the common speculations about the next generation of LLMs is the potential for trillion-parameter (densely activated) models, given the exponential parameter growth in the last 5 years:

LLMs have roughly grown parameter count 10x each year, but many have not varied the size of the training data sets significantly:

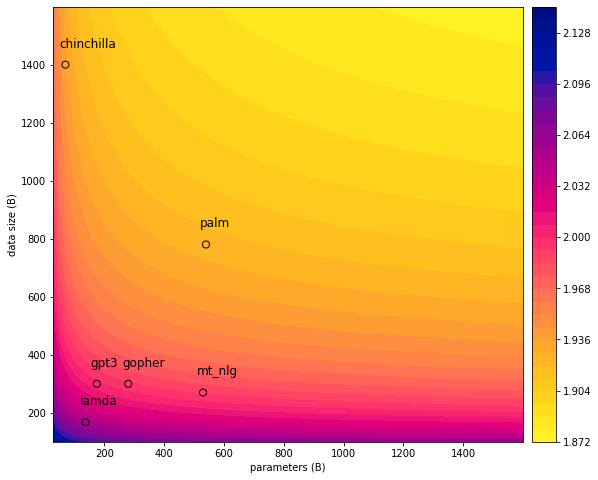

However, more recent literature suggests that the focus on scaling parameter count has not been the best way to maximize performance, given fixed computational resources and hardware utilization (i.e. to train a “compute-optimal” model):

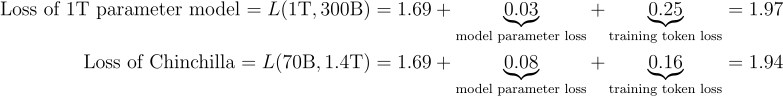

Fitting a parametric function to their experimental results, Google DeepMind researchers found to minimize the model loss L (i.e. maximize performance) that the number of parameters N and the training token count D should be increased at roughly the same rate:

The authors also trained a model named Chinchilla (70B parameters) with the same computational resources as Gopher (280B parameters) but on 1.4T tokens instead of 300B tokens, outperforming significantly larger models with the same FLOPs budget and thereby also proving that most LLMs were overcompensating on compute and starved for data.

With 60% fewer parameters (and thus inference compute requirement) than GPT-3, Chinchilla still easily outperforms the 175B model.

In fact, if we trained a 1T parameter model with the same 300B token dataset as GPT-3, we would still expect such a model to underperform Chinchilla:

The relative magnitudes of the respective loss terms for the 1T parameter model (0.03 model parameter loss vs. 0.25 training token loss) also suggest that the marginal benefit from increasing the model size is lower than from increasing data volume.

Going forward, much more performance can be gained by diverting incremental computational resources to train on larger datasets of comparable quality than to scale up model parameter count.

Cost/FLOP efficiencies

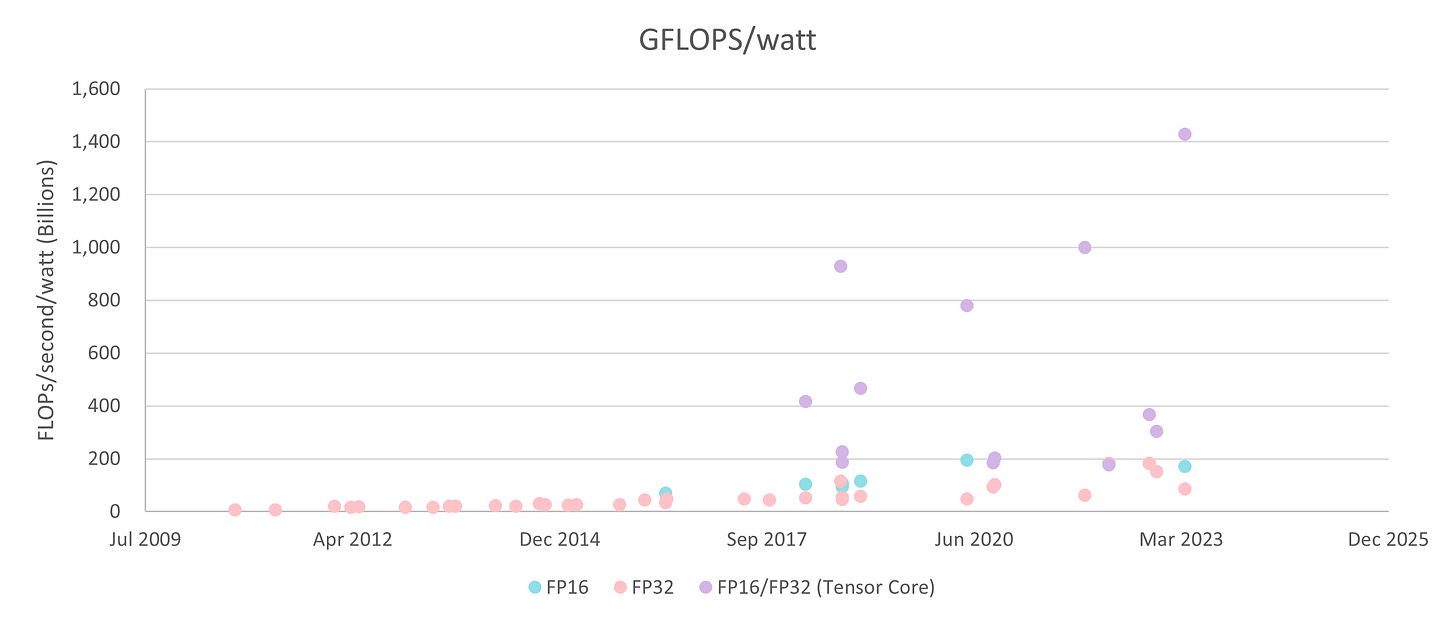

For LLM training, the most important hardware performance metric is realizable mixed-precision FP16/FP32 FLOPS. Hardware improvements have been aimed at minimizing cost while maximizing 1) peak FLOPS throughput and 2) model FLOPS utilization. Although both areas are intertwined in hardware development, to keep our analysis simple we will focus on throughput here and discuss utilization in the next section.

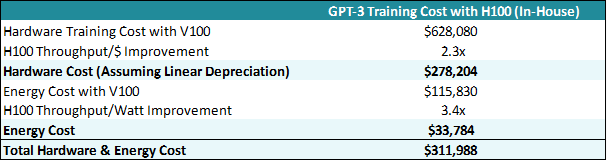

So far, we have approximated Cost/FLOP by looking at cloud instance pricing. To drill down further, we assess the cost of running these machines ourselves, with the primary components being 1) hardware purchase and 2) energy expense. To illustrate, we again go back to GPT-3, which was trained for 14.8 days by OpenAI on 10,000 V100 GPUs in Microsoft Azure22:

On hardware cost, Huang’s Law (per Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang in 2018) stated that GPUs were growing 25 times faster than five years ago.23 In the context of LLM training, much of this performance boost was driven by the advent of Tensor Cores (in the case of AMD, matrix cores), which have enabled significantly more performant and efficient mixed-precision operations by processing matrices instead of vectors as the computation primitive. Nvidia first introduced Tensor Cores in 2016 with the V100 data center GPUs. Although the improvement is less significant compared to the jump from the initial introduction of tenor cores, each successive generation of Tensor Cores has furthered throughput/$. Today, we are still seeing 50% generation-over-generation throughput/$ improvement (or ~22% per year) for the data center GPUs used to train LLMs:

Energy efficiency is improving even faster. Today, we are seeing 80% generation-over-generation throughput/watt improvement (or 34% per year) for the data center GPUs used to train LLMs:

Based on the improvements from the V100 (with which GPT-3 was trained) to the upcoming H100 alone, we would expect the in-house training cost to be 58% lower ($312k instead of $744k).

Going forward, we anticipate continued design innovations to drive discontinuous improvements to both hardware cost and energy efficiency. For example, going from the V100 to A100 GPU Nvidia added sparsity features that further improve throughput by 2x for certain deep learning architectures.24 In the H100, the company is adding native support for FP8 data types, which can lead to further throughput improvements when combined with existing techniques like quantization for inference.25

Additionally, we have seen the emergence of TPUs and other specialized chips that fundamentally redesign the chip architecture for deep learning use cases. Google’s TPU is built on a systolic array architecture that significantly reduces register usage, improving throughput.26 As we will see in the next section, many of the recent hardware improvements have been aimed at improving hardware utilization as we scale training and inference to large parameter models.

Hardware utilization improvements

One of the major challenges in LLM training has been the need to scale these models beyond a single chip to multiple systems and to the cluster level, due to the significant memory requirements. For context, in a typical LLM training set up the memory required to hold the optimizer states, gradients, and parameters is 20N, where N is the number of model parameters.27

Thus, BERT-Large, one of the early LLMs from 2018 with 340M parameters, required only 6.8GB of memory, easily fitting into a single desktop-class GPU. On the other hand, for a 175B parameter model like GPT-3 the memory requirement translates to 3.5TB. Meanwhile, Nvidia’s latest data center GPU, the H100, contains only 80GB of high bandwidth memory (HBM), suggesting that at least 44 H100s are required to fit the memory requirements of GPT-3.28 Furthermore, GPT-3 required 14.8 days to train even on 10,000 V100 GPUs. Thus, it’s essential that FLOPS utilization remains high even as we increase the number of chips for training.

The first dimension of hardware utilization is on the single-chip level. When training the GPT-2 model on a single A100 GPU, hardware utilization reached 35.7%.29 One of the hardware utilization bottlenecks turns out to be on-chip memory and capacity: Computations in processor cores require repeated access to HBM, and insufficient bandwidth inhibits throughput. Similarly, limited local memory capacity can force more frequent reads from the higher latency HBM, limiting throughput.30

The second dimension of utilization relates to chip-to-chip scaling. LLM training for models like GPT-3 requires partitioning the model and data across many GPUs. Just as bandwidth for on-chip memory can be a bottleneck, the bandwidth for chip-to-chip interconnects can also be a limiting factor. Nvidia’s NVLink enabled 300GB/s of bandwidth per GPU with the release of V100. This figure increased 2x for the A100.31

The last dimension of utilization is system-to-system scaling. A single machine holds up to 16 GPUs, so scaling to a larger number of GPUs requires that the interconnects across systems do not bottleneck performance. To this end, Nvidia’s Infiniband HCAs have increased max bandwidth by 2x in the last 3 years.32

Across the second and third dimensions, the software partitioning strategy is a crucial consideration for effective utilization. Through a combination of model and data parallelism techniques, LLM training at the cluster level for Nvidia chips reached 30.2% model FLOPS utilization with MT-NLG in Jan 2022,33 compared to 21.3% in 2020 with GPT-3.

Specialized hardware like TPUs has achieved even greater efficiency.

Google’s 540B parameter PaLM model achieved 46.2% model FLOPS utilization on the TPU v4 chips, 2.2x GPT-3’s training utilization.34

This utilization improvement was fueled both by more efficiently parallelized training (with Google's Pathways ML system) and by the fundamentally different architecture of the TPU itself. The chip's systolic array architecture and the significant local memory density per core reduce the frequency of high-latency global memory reads.

In a similar vein, we have seen companies like Cerebras, Graphcore, and SambaNova allocate significantly larger amounts of shared memory capacity in-processor. Going forward, we expect other emerging innovations - such as scaling chips to wafer scale for latency reduction/increased bandwidth, or optimizing data access patterns through programmable units - to further push the hardware utilization envelope.35

Other algorithmic improvements have also been important: Nvidia researchers in a May 2022 paper reached 56.0% model FLOPS utilization for subsequent training of MT-NLG, by selectively recomputing activations rather than relying on traditional gradient checkpointing. The experiments were conducted using 280 GPUs (instead of 2,240 in the original case) and without data parallelism, but nonetheless demonstrated a significant performance improvement over the original run with 30.2% model FLOPS utilization.36

Parting thoughts: LLMs are ready for prime time

The NYTimes recently reported that Google had declared ChatGPT a “code red” for its search business.37 From the economic lens, our rough cost estimate that incorporating performant LLMs into search would cost ~15% of query revenue suggests the tech can already be feasibly deployed. However, Google's dominant market position also disincentivizes it from being a first-mover: at $100B+ of search revenue, widespread deployment of the technology would dent profitability by $10B+. On the other hand, it's unsurprising that Microsoft is planning to incorporate LLMs into Bing.38 Even though the cost structure is higher than traditional search, LLM-powered search is not loss-making and the company has a significantly lower search engine market share today. As a result, if Microsoft succeeds in taking share from Google the end result would likely still be greater profit dollars, even as serving existing queries becomes more expensive.

For other products, interestingly LLMs can already be profitably deployed with SaaS-type margins. For example, Jasper.ai, which was recently valued at $1.5B and uses LLMs to generate copywriting, charges ~$82/100K words (the equivalent of ~$1.09/1000 tokens).39 Using OpenAI's Davinci API pricing of $0.02/1000 tokens, gross margins are likely well above 75% even if we sample multiple responses.

It’s also surprising that GPT-3 can be trained with only ~$1.4M today in the public cloud, and that the cost of even state-of-the-art models (like PaLM at ~$11.2M) is not prohibitive for larger companies. With training costs dropping >80% over the last 2.5 years for a GPT-3 quality model, training performant LLMs will likely become even more affordable. In other words, training LLMs is not cheap, but it’s also not a game of significant economies of scale, entailing massive upfront capital spending that gets amortized over years. Rather, the “Chinchilla” paper suggests that going forward one of the emerging scarce resources for training LLM is not capital, but the volume of high-quality data, as scaling model parameter count delivers diminishing returns.

(2/9/23 Edit: Thank you to Nvidia’s Emanuel Scoullos and Ioana Boier for suggesting the inclusion of “Reducing Activation Recomputation in Large Transformer Models” in our discussion on model FLOPS utilization)

ChatGPT: Optimizing Langauge Models for Dialogue

In practice, ChatGPT also uses RLHF on top of the base 175B parameter language model, but for the sake of simplicity we won’t consider the reinforcement learning cost

Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models

For encoder-decoder models, inference FLOPs is ~N (instead of 2N as per decoder-only models)

Everything described for FP16/FP32 also applies to BF16/FP32 mixed-precision operations, which are supported with similar throughput on the A100 and other processors

Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models

For encoder-decoder models, training FLOPS is ~3N (instead of 6N as per decoder-only models)

Assuming 20 bytes of memory per parameter based on using the Adam optimizer with mixed-precision training

Hi Jiayu - certainly, and I would love to take a look at the translated post as well!

Regarding the "cache hit rate of 30%" part, if I understand correctly, "cache hit" means no actual search happens, right? If so, this means 30% of the searches actually cost nothing & the related revenue is 100% profit. Accordingly, take ChatGPT-Equivalent search for example, with a overall 75% profit margin, the cost of each actual search should be "0.055 * (1- 75%) / (1 - 30%) = 0.020", not "0.055 * (1- 75%) * (1 - 30%) = 0.010"